Spotlight John Snyder

Spotlights

We are honored to Spotlight John Snyder, Montessorian, Guide, and Author. As a parent and guide, John has many insights into Montessori life that he graciously shares in his book, Tending the Light and here with us in this interview. We hope you enjoy!

Q: Can you tell us a little bit about yourself? Your background, your interests, your dreams?

I was born the last day of 1954, which put me near the end of the generation that was decimated by the Vietnam War. I was a conscientious objector, but, fortunately for me, the draft ended just before I had to argue my case to the very hawkish local draft board. In any case, my views on war were formed early and have never wavered.

I remember being strongly attracted to music, especially classical music, even as a very young child, but my family was not musical, and I spent most of my childhood dreaming of becoming a scientist. My father was an analytical chemist who worked at oil refineries in West Texas. These were the days before OSHA, and my mom and I used to drive into the refinery every day to bring him his lunch at the laboratory. He and the other guys in the lab would show me things and let me look through the spectrophotometer. For a while my hero was Enrico Fermi because I had a book about great scientists and thought he looked like a nice guy. Some of the older ones with big beards and stern faces weren’t so appealing.

I began to learn the violin in sixth grade and reconnected very strongly with my earlier love of music. It’s not an exaggeration to say that music is what got me through adolescence alive, and my dream as a young man was to be an orchestral conductor and composer. I double majored in music and computer science as an undergraduate and worked for a number of years as a programmer. Along the way I developed a strong interest in the mathematical and philosophical foundations of computing – think Alan Turing – and eventually earned graduate degrees in theoretical computer science and philosophy.

I married young, but my wife Kathleen and I waited 12 years to have our first and only child, Karl. In retrospect I think that worked out very well both for us and for Karl.

Q: Now that the hardest question is out of the way: What’s your favorite color?

Whatever color is most appropriate for the situation. That being said, I am very partial to aqua blue and teal.

Q: Do you have a favorite book? How about a film?

In the fiction category, I love short stories, especially the short stories of Flannery O’Connor, Doris Lessing, Ursula Le Guin, and James Joyce. In nonfiction, I love to read science books. The Ancestor’s Tale by Richard Dawkins is a favorite. The books of Thich Nhat Hanh, such as Being Peace and The Miracle of Mindfulness, have also been important to me. I’m not really a movie buff, but Wings of Desire is a favorite. The scene with the angels in the library is definitely my favorite scene from any movie. I get a lump in my throat just thinking about it.

Q: When you close your eyes late at night, and imagine waking up and starting a new adventure: what is that adventure?

I don’t dream of new adventures; I dream of being able to complete the marvelous Montessori adventure I was on when I was diagnosed in 2011 with ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease). Fortunately, progression of the disease has been gradual, and I was able to work for two more years at Austin Montessori School before I had to retire. Around the same time, I also stepped down as chair of AMI-EAA, the professional organization for AMI-trained elementary teachers, and I relinquished my place as a charter member of the Montessori Leadership Collaborative, where I had the privilege of working with leaders of all the major Montessori organizations in the US.

Forced retirement is still retirement, and it gave me the time to complete two big Montessori projects: leading a team of about 50 experienced Montessorians to map the Common Core State Standards to a representative AMI elementary curriculum – the result can be found on the AMI/USA website – and publishing Tending the Light: Essays on Montessori Education, a collection of fifty articles I had written about the Montessori elementary over the previous fifteen years. In 2012 I was able to make one last trip abroad to do a keynote address and workshop in Vienna for the Austrian Montessori Association. I dream of being able to do more wonderful trips like that!

My last publishing project is a book of my poems written over the last thirty years, called Infinity Minus One. I hope to have it available on Amazon sometime in June.

Q: What first appealed to you about Montessori?

The idea of a completely nonviolent form of education in which children were treated with the same kind of respect afforded to one’s most cherished adult friends and colleagues.

My family came to Montessori a bit late. My son was already five years old when we enrolled him in a Montessori school. The guide, Rebecca Lowe, was skeptical about taking in an older child with no Montessori experience, but she agreed to meet with Karl in the prepared environment after school to get a sense of who he was. After the meeting she said, “He’s a natural.” I’m still brimming over with gratitude to her for accepting him into her community. If she hadn’t, I doubt that I would ever have worked in Montessori.

“These children would grow up knowing how to collaborate, share power, take care of everyone in the group, and find their own success in the success of others.”

When my son entered Montessori, I was working as a management consultant, helping executives and project managers learn first principles of collaboration. It was very hard work and progress was slow. Often these executives were bringing down their companies because of their inability to collaborate and share power, so the stakes were high. I would come home from one of these gigs and observe in Karl’s early elementary class, where I would see seven and eight-year-olds doing perfectly well what we could just barely teach our adult clients to do. At some point it dawned on me that there, in the Montessori classroom, was where the leverage was. These children would grow up knowing how to collaborate, share power, take care of everyone in the group, and find their own success in the success of others. They wouldn’t need expensive consultants. It would be in their bones.

Q: It sounds like you did not start out intending to be a Montessori Guide. What was the catalyst for this career change?

My management consulting work was strenuous, and after a few years I was burning out. I gave myself six months off to explore what I wanted to do with the rest of my work life. I was exploring widely and talking to a lot of different people about what brought them to their professions. What kept coming up for me was teaching. I was beginning to look seriously at becoming a high school math teacher.

About the same time, our Montessori school lost its only elementary guide to retirement. My wife and I began looking for another school where my son could finish out the elementary and even stay in Montessori through early adolescence. At Austin Montessori School we observed in the early elementary, the upper elementary, and the adolescent community. I remember being charmed by the children of the upper elementary who served us tea and so graciously welcomed us to their classroom. Little did I know that in a few years I would be the guide of that class!

At the adolescent community, I met Don Goertz, founder of the adolescent program. I knew Don only by reputation, but I knew that he had had a long career as a professor of classics before coming to work with Montessori adolescents. I asked if he would be willing to spend a few minutes with me sometime telling me how the transition had worked for him, since I had a similar background and was considering a high school teaching career. Don took me by the arm, led me into the kitchen, and proposed that I get Montessori training and come work with the adolescents at Austin Montessori. In the moment, I was stunned, but after thinking about it for a while, I contacted him and set up a meeting with him and his wife Donna, founder of the school.

At that time, there was still no formal training or orientation for Montessori adolescent work, so we agreed that I would take AMI primary training over three summers, and in the intervening academic years, I could work as Donna’s assistant in the early elementary. After a year of primary training and working as an assistant, the school asked if I would consider switching to elementary training and working with the upper elementary. I agreed, and that’s how I became a Montessori elementary guide.

Q: You were hired to work with adolescents, but ended up working with Upper Elementary students, children age 9 to 12. What appeals to you about this particular age?

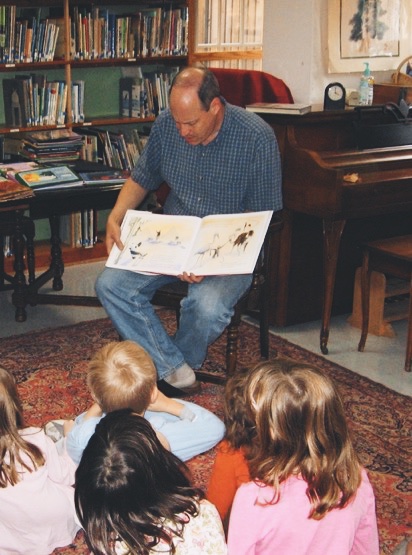

There is a chapter in my book that answers that question at some length, but the short answer is that the Upper Elementary is the time I think of as the flowering of childhood. All the hard work that the children and their primary guides did and all the hard work that the children and their early elementary guides did now comes to fruition as childhood finishes its work and yields the floor to adolescence. Children who entered my community at age 9 were still very much children; when they left at age 12, most of them were adolescent. As an upper elementary guide, I had the privilege of seeing and supporting the transition to adolescence.

The children of the upper elementary are incredibly capable. They need and love a good challenge. This is the time for big, ambitious projects, and also for consolidation of skills that began developing in the early elementary. New powers of cognition, reflection, and instruction come online over the three-year period, and the children sense that and want to vigorously apply them to things that they care about.

These older children are, by virtue of their growing abilities, ready to take on more and more responsibility not only for their own education, but also for the health and well-being of their classroom communities. The guide’s challenge is to balance freedom and responsibility in the community such that the children are always working right at the limits of what they can manage on their own, without getting in over their heads.

There are new powers of language, self-expression, and reasoning that must be strongly exercised. The guide’s work is to provide opportunities, support, and positive channels for that work. Otherwise, the children can suffer from their own and others’ unskillful attempts to come to terms with these new powers. This period of childhood has sometimes been called “the age of rudeness.” But that’s an adult value judgment. From the child’s perspective, it has more to do with lack of skill, compounded with the ongoing and relentless redefinition of one’s self both as an individual and as a social being. This, of course, is just a prelude to the intense psychological work that goes on in adolescence.

“There were days in the classroom when nothing went as I planned or expected. I learned eventually to let go of my need to control things in the classroom and simply look to see what the children were doing.”

The 9 to 12-year-olds are also practicing other vital social skills, such as knowing when to show themselves and when to withhold. The younger elementary children are still quite transparent and concrete, but the older ones can be enigmatic. You can also observe these children trying on different personae as part of their work of discovering who they are and how relationships work. This can be challenging for parents, and part of the work of the upper elementary guide is to help parents understand and navigate these years.

Q: What advice do you have for new Montessori adults?

I spent my first year in Montessori as the assistant to Donna Bryant Goertz in her 6-9 class. It was both exciting and humbling. A few days into our work together, Donna said to me, “Be prepared to discover that almost every instinct you have about working with children is misguided. It’s like that for all of us who grew up outside of Montessori. Even after decades of Montessori, I still find myself responding out of my old conditioning. Please don’t take it personally when I correct you or show you a different way of being with the children.” She was right. There was a lot to learn and even more to unlearn. It takes time and patience with oneself to learn to see children as Dr. Montessori saw them.

Q: What inspired you to share your story in your Book and on your Blog?

Donna saw right away that I was a writer, and she encouraged me to write about Montessori. My first Montessori article to be published by AMI/USA was an article on guidelines for computer use in the Montessori home. An updated version of that article is in my book. The late Denny Schapiro, publisher of the quarterly Public School Montessorian, saw some of my posts on an online Montessori discussion forum and offered me space in his publication to write a regular column. The articles I produced for him over the next eight years form the core of my book. Other articles were written for the parents at Austin Montessori School. Still others came from keynote addresses and workshops that I offered over the years.

“I always had a sense of how blessed I was to be working in a Montessori school where the conversation was about each other’s latest Montessori moments and breakthroughs.”

When I retired, a number of Montessori friends and colleagues approached me with offers of help to put a book together. Ultimately, the leadership of the four AMI affiliate organizations in the US – NAMTA, AMI/USA, MAA, and AMI-EAA – all helped fund the publication, with David Kahn of NAMTA as the primary sponsor and publisher. I could not have been happier with the result.

I have always tried to write to address specific needs that I saw or that had been explicitly expressed to me. I think this is why people still find the essays relevant and helpful. Writing was also a way for me to pass on the wealth of information and good advice that I had received from experienced Montessorians during my formative years.

Q: Did you have a “Montessori Moment?”

I had them almost daily when I was in the classroom. The children were always showing me new things. I already spoke about one moment I had observing the skillful collaboration of the children in my son’s early elementary class. I wrote about another Montessori moment in an article called “A Closer Look” that is in my book and also on MariaMontessori.com.

My mom was a fourth grade teacher in traditional public and parochial schools. She used to describe how conversation in the faculty lounge was so often trading “war stories” about the children and parents and how discouraging that was. So I always had a sense of how blessed I was to be working in a Montessori school where the conversation was about each other’s latest Montessori moments and breakthroughs.

Q: What’s your favorite Montessori quote?

The title of my book, Tending the Light, is an allusion to my favorite Montessori quote about the elementary, a statement I have come to think of as Montessori in a nutshell: “Our care of the child should be governed, not by the desire ‘to make him learn things’ but by the endeavor always to keep burning within him that light which is called the intelligence”. That’s from The Advanced Montessori Method, Volume 1. There were days in the classroom when nothing went as I planned or expected. I learned eventually to let go of my need to control things in the classroom and simply look to see what the children were doing. It may not be what I had planned, but could I see “the light which is called the intelligence”? If so, then I knew it was a good day and the children were well served.

Q: What advice do you have for new parents trying to incorporate Montessori at home?

We know from Dr. Montessori’s own work with the poor in Rome and our contemporary Montessori schools that serve at-risk, under-resourced populations that Montessori education can work wonders in a child’s life even if their home environment is not ideal. However, there is no doubt that the very best results for the child come from a partnership of home and school, where both are aligned to support the developmental needs of the child. For some families such alignment may mean just a little fine tuning of home life, but for many it may entail significant changes.

My advice to families is to work closely with the Montessori guides and school administration to understand what sort of home life best supports the child’s work at school and to prioritize the changes that need to be made. Ask the guides, “If we could make one change at home that would help my child at school, what would it be?” More sleep? Better nutrition? A more consistent schedule? Rethinking discipline? Less exposure to TV, computers, and video games? More time outdoors? Then work on changing one thing at a time.

Different schools will have significantly different capacities to support parents in such changes, so ask the guide or administrator to introduce you to parents at your school who have a lot of experience creating a Montessori home life. Read Patricia Oriti’s book At Home with Montessori, available from NAMTA. Search the archives at MariaMontessori.com for articles related to the partnership of home and school, such as Donna Bryant Goertz’s “Owner’s Manual for a Child” or Sveta Pais’s “Journey of a Montessori Parent”.

Q: What do you think is the best introduction to Montessori?

Without a doubt, seeing is believing when it comes to Montessori education. You can read all the Montessori articles and books in the world, but until you have sat in a high-functioning Montessori classroom at each level and felt the peace, the joy, the excitement of the children, it is very hard to understand how profound this way of working with children really is. Take a handkerchief, because many first-time observers, including myself, leave the classrooms in tears, saying to each other, “If only I could have had a school like this when I was a child! I never knew such a thing was possible.”

“…Montessori education allows children of all ages, backgrounds, and temperaments to flourish, to become well-rounded, whole human beings, comfortable in their own skin and able to handle whatever life brings them.”

But books and articles are good, too. MariaMontessori.com has a wealth of introductory pieces for the various levels. Paula Polk Lillard’s classic books continue to be a good place to start. For those who want to sample Dr. Montessori’s own work, I recommend The Secret of Childhood, The Discovery of the Child, and Education for Peace.

Q: What continues to inspire you about Montessori?

Two things, really. First, the thing that everyone around a Montessori school sees (especially if the school serves all ages, including adolescence); namely, the way Montessori education allows children of all ages, backgrounds, and temperaments to flourish, to become well-rounded, whole human beings, comfortable in their own skin and able to handle whatever life brings them.

“There was a lot to learn and even more to unlearn”

Second, the way that working with children in the Montessori way transforms the adults, both teachers and parents. I know of no other work that allows one such opportunities to learn about oneself, to grow, to heal, to rise above one’s conditioning and circumstances. This is the gift of the children to those adults who give themselves to meeting the children’s profoundest needs.

Q: In what ways do you envision the future of education? Where do you see Montessori in the next 100 years?

Those are really hard questions. My crystal ball sputters and goes dark when it hears those questions. It’s not that it’s difficult to extrapolate current educational and Montessori trends into the future; it’s that I do not know into what future I am extrapolating. Most of our planning continues to go merrily along assuming the future will be much like the present, but the one thing I am confident of with regard to the future is that it will not look very much like the present. As best I can tell, we have driven this planet and our human societies into completely unknown territory in a number of important respects.

When I was born there were 2.7 billion people on the planet; now there are 7.4 billion and rising. No one knows exactly what the human carrying capacity of the planet is, but the best estimates are around nine or ten billion, and we are on track to reach that limit by 2050. Simultaneous with this milestone, we will see climate change driven by global warming redefine the geographical, political, economic, and resource maps of the world, with uncertain outcomes for all.

If history is any guide, we can expect that education, which is already underfunded in this and many other countries, may become an even lower priority as governments struggle to meet other challenges. We will need to advocate even more strongly for the children. I suspect we may also need to reinvent the way we organize Montessori education. The two dominant models are the publicly funded government school and the privately funded boutique school. Neither of these models strike me as what the future will need from us. We may need to go back to first principles – what are the developmental needs of children at each age? – and develop completely new ways of meeting those needs appropriate to the very different context in which we may find ourselves and our families.

“When times are uncertain and we don’t know for which future we are preparing today’s children, the best we can do is to offer education that leads to creativity, resilience, moral strength, servant leadership, skill in conflict resolution and teamwork, respect for the views, rights, and freedoms of others, a long view of human history, and faith that human beings working together can create a just world.”

There are a couple of educational trends that I think will continue to develop in the foreseeable future. On one hand you will continue to see an accumulation of knowledge in developmental and cognitive psychology, along with the results from brain science. In most cases these new developments will support traditional Montessori practice, and in other cases our practice may need to be revised in light of them. On the other hand, we will continue to see a larger and larger gap between what research is showing us that children need and the way educational establishments around the world operate their factory model schools. I can’t predict how this tension will ultimately resolve, but the best course for us, I think, is to continue to advocate for the child and be ready to step in with our successful developmentally-based model wherever there is even the smallest opportunity. We also need to get our message out to more parents, especially those not in our schools, because parents may have to shoulder even more of the responsibility for meeting their children’s needs when social institutions, for whatever reason, fail.

When times are uncertain and we don’t know for which future we are preparing today’s children, the best we can do is to offer education that leads to creativity, resilience, moral strength, servant leadership, skill in conflict resolution and teamwork, respect for the views, rights, and freedoms of others, a long view of human history, and faith that human beings working together can create a just world. I know of no educational approach that does that better than Montessori. Most don’t even come close.

Written by:

Baan Dek