Watch and Wait

Thoughts & Reflections

On May 6, 1952, Maria Montessori passed away in the village of Noordwick aan Zee, on the North Sea, in the west of the Netherlands. As with those who were brave enough to live, great stories are told of how they met their end. In Rita Kramer’s biography, Montessori’s last moments are recounted thus:

“Maria had been thinking of making a trip to Africa, but it had been suggested that because of the state of her health she ought not to travel but arrange instead for her lectures to be given by someone else. Mario was with her and she turned to him and said, “Am I no longer of any use then?” An hour later she was dead of a cerebral hemorrhage.”

Three years before, at the Sorbonne in Paris, Montessori was awarded the Legion of Honor from France. She was also nominated for the Nobel Peace Price in 1949, 1950 and 1951, respectively. It was a time of great hope and promise – a certain sense of renewal and dedication to the future was everywhere self-evident.

The life of Maria Montessori, to be sure, was replete with travel and adventure. There was a great sense of personal and professional achievement. Yet, her singular purpose was a fearless commitment to see her newly discovered science of education disseminated across the world. Of course, her ambition was not merely to spread her observations, it was much more centered on how to empower children to follow their interests.

Montessori trusted that while her original insights would eventually be validated by science, as indicated by her global recognition, what mattered most wasn’t the method, practice or even implementation, but rather, the adoption by children. If the Montessori approach to education was to be truly successful, it would have to be at the hands of children.

It wasn’t teachers, or even parents that would see to the success of Montessori. No, it was future generations. It was, as Montessori might have said, not the fact that society was focusing its attention, but rather, what that attention was pointed towards: the child. The child held promises that had long since expired, or in the least faded away, in adults. Nevertheless, everyone could readily identify in the child, the outlines of what was to come.

Rita Kramer makes the case that, “An educator and teacher, Montessori ended her life by saying that neither teaching nor education brings about the child’s development.” Kramer continues, in a somewhat radical and far-seeing summary of the Montessori philosophy, one that contains the heart of what makes this approach so special:

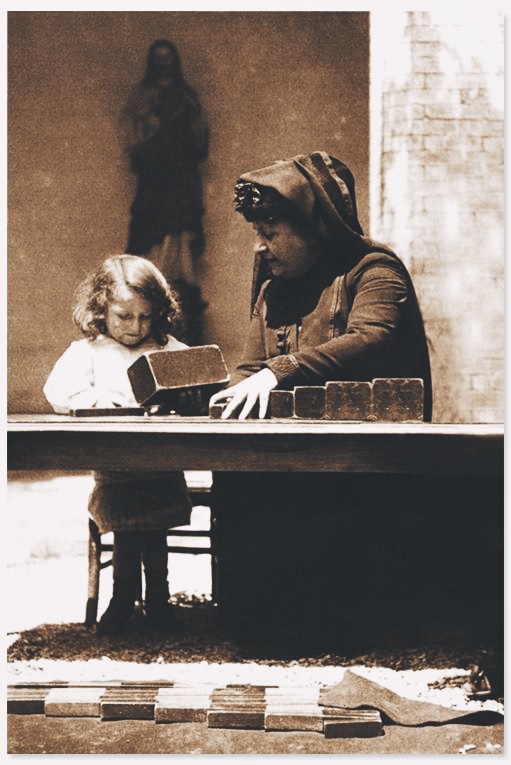

“ all educators and teachers can do is refrain from placing obstacles in the child’s path by providing him with an environment in which he is “free to create himself ”

As we look back and reflect on this magnificent life Montessori led, with the vantage point of nearly three quarters of a century, we are humbled by her project and her willingness to, even at her last moment, engage in the noble effort to spread a different set of values throughout the world.

Montessori was once asked to sum up her new approach to education. “Attendee, osservando – watch and wait.”

Written by:

Bobby George