Montessori and Peter Pan

Thoughts & Reflections

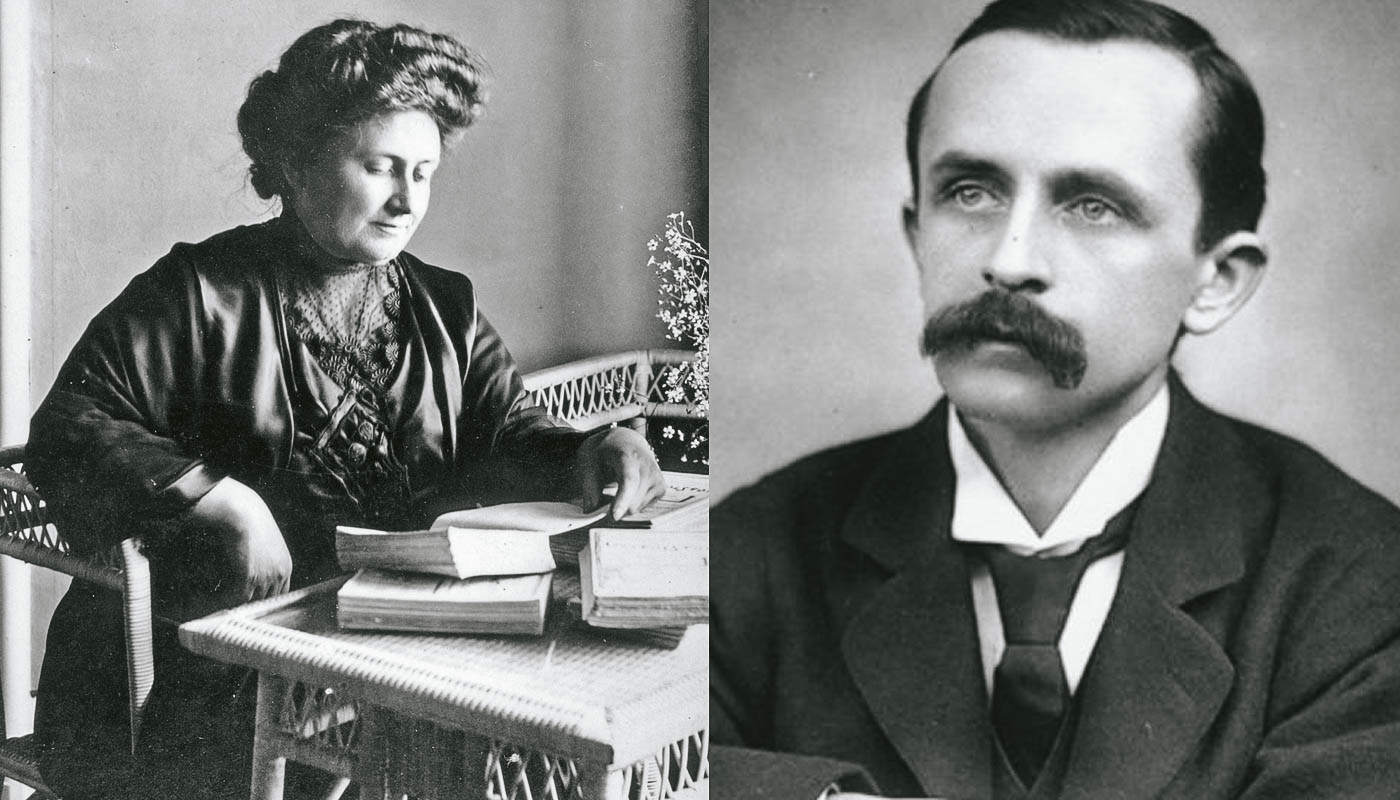

Maria Montessori, Italian educator and physician, pioneered the Montessori method and philosophy of learning. J.M. Barrie, Scottish novelist and playwright, authored the childhood classic Peter Pan. The former is grounded in logic, independence, and reality, the latter is the defining example of whimsy, imagination, and “never growing up.”

While on the face of it these two historic figures have more to disagree about than to agree about, in particular their thoughts about fantasy versus reality, I think they actually have a fair amount in common.

Namely, Montessori and Barrie share a willingness to strike logic into the heart of adulthood, to shake us out of our habitual modes of thinking, particularly as it pertains to what it means to be a child, lest we forget that we were once children too.

Montessori may often be characterized as empowering children to take on more responsibilities, such as by utilizing glass and other breakable materials, though at the core of her philosophy is the idea that true learning happens when children are allowed to follow their interests, when they are allowed to be themselves.

For Barrie, Peter Pan is a healthy reminder, not that we should learn to fly, or that children should try to jump off their rooftops and reach Neverland, but that we should try, as adults, to tap into the possibilities of childhood that we once knew and readily embraced.

As adults, we make many assumptions about childhood. One of these assumptions is that childhood is a phase of life that must be overcome. Of course, there are very practical reasons to want to achieve adulthood, i.e,: health and well-being. But, there are other assumptions too, assumptions that I think Montessori and Barrie would both say are too readily dismissed: i.e. that adults can learn how to embrace their childlike wonder.

What do we lose when we grow up?

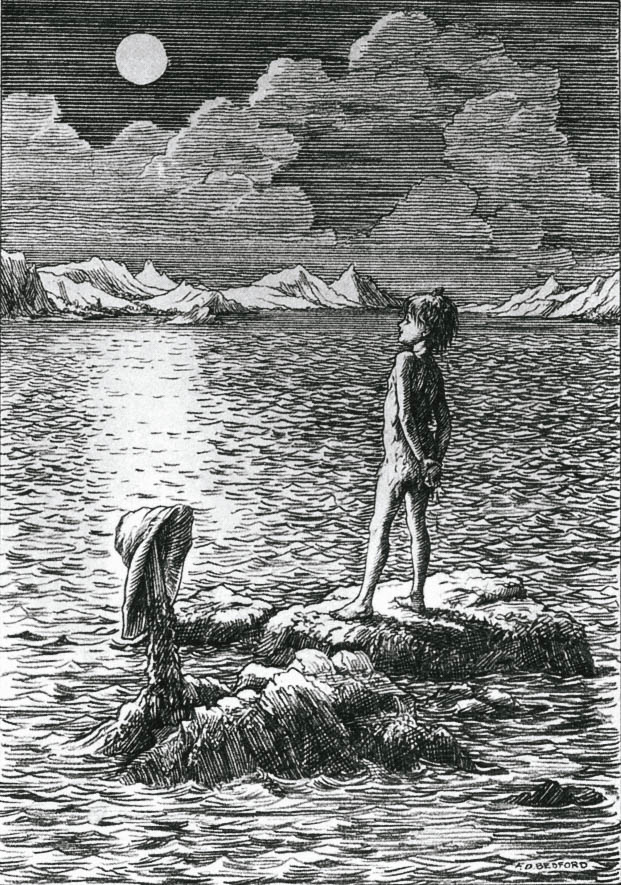

Perhaps the most popular manifestation of this movement of thought comes from Peter Pan, the story of a boy who refuses to grow up. Written in the early part of the twentieth century, Peter knows how to fly and his spirit takes him and his dear friend Wendy to the island of Neverland, where they go on great big adventures.

In a memorable passage, when Wendy has long since grown up and forgotten how to fly, her inquisitive daughter sets the stage:

“Why can’t you fly now, mother?”

“Because I am grown up, dearest. When people grow up they forget the way.”

“Why do they forget the way?”

“Because they are no longer gay and innocent and heartless. It is only the gay and innocent and heartless who can fly.”

As adults, we’ve comfortably and often unquestionably grown into our assumptions, much in the same way we rather uncomfortably outgrew our childhood. Needless to say, these assumptions are derived, not from our experiences of childhood, but from our conceptions of adulthood.

While, at times, we may act childish as adults, and have momentary lapses where we are giddy with joy and whimsy flutters about, we usually live rather steadfastly in a world where the unwritten rules of childhood do not apply. In the words of Wendy, we are no longer gay and innocent.

Invariably, we come to envision childhood as that which must be grown out of. We outgrew it, we tell ourselves. One day, we tell our children, you will outgrow it too. In our weakest moments, we exclaim to our children, “When will you grow up!” Of course, there are also times when we lament this growth. We look upon our children and hope they never grow up. We remind ourselves to enjoy every moment.

At the end of the day, we want nothing more than to protect our children from our mistakes. We share our lessons, our struggles no less than our triumphs, in the spirit of helping our children avoid the same obstacles we encountered. We want to give them a leg up. We want to feel assured that if they encounter issues, they’ll know how to figure it out. We will have helped them along the way.

“Where we, as adults, see barriers, or obstacles, or difficulties, children see opportunities.”

Childhood is in each and every one of us. At one point, we were children. And yet, the older we get, the farther away we become – not just in terms of time, but also in our abilities to see and relate to the world as children do. As the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze writes in, What Children Say,

“Children never stop talking about what they are doing or trying to do: exploring milieus, by means of dynamic trajectories, and drawing up maps of them”.

They’re always exploring the world around them, trying to figure things out as they go along. Everything is new and exciting, and they want to taste it, and feel it, and see it – always for the very first time. Nothing is more new than the ordinary and everyday. If only we could learn to see the world with their mouths, fingers and eyes. If only we had the same confidence in our mistakes.

Where we, as adults, see barriers, or obstacles, or difficulties, children see opportunities. Where we see weight and unhappiness, they see joy and lightness. Children approach the world very differently than we do. If only we could learn to see the world through their eyes once more. Who knows how to approach problems more creatively than children? We have so many assumptions of childhood. One assumption I think we should keep, is that we have so much left to learn.

“Genius is the recovery of childhood at will.” – Rimbaud

Written by:

Bobby George